Once Deemed a “Needed Win” U.S.-Supported Operation Failed to Net Cartel Chief in 2010

Mexico’s “largest air mobile operation” “caused both civilian and police deaths” but seen as “overall success” for President Calderón and “serious blow” to drug cartel

This post was co-authored by Michael Evans and Jesse Franzblau and was prepared in collaboration with MVS Noticias in Mexico.

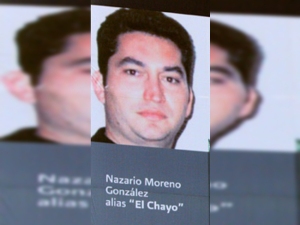

The Mexican government unleashed a wave a déjà vu across the country last week in announcing the killing of Nazario Moreno González (“El Chayo”), a feared drug cartel chief who was first pronounced dead three and half years ago in a massive police operation that the U.S. Embassy characterized at the time as a “needed win” for then-president Felipe Calderón.

Assuming that it sticks this time, this most recent killing of El Chayo is another notch in the belt of current President Enrique Peña Nieto following the recent re-capturing of another top drug lord, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, who had escaped from prison in 2001. The surprise announcement also raises questions about the massive, U.S.-backed, Mexican police operation in December 2010 that was believed, until recently, to have ended with El Chayo’s death. Hailed in a contemporaneous U.S. Embassy cable as an “overall success” and a shining example of improving U.S.-Mexico security cooperation under the Mérida Initiative aid package, the so-called “Coordinated Michoacan Operation” of 2010 now seems like another in a long line of failed government efforts to pacify the long-troubled region.

By the end of 2010, Mexican President Felipe Calderón needed a big win. The country’s security situation had become increasingly chaotic. Drug cartels had supplanted the police in many parts of the country, openly exercising control over federal highways and town squares along key transportation routes. The conflict between rival cartels and government security forces had left thousands dead or missing. Most vulnerable and hardest hit amid the waves of violence were migrants, many from Central America, who traveled along those same routes and were easy prey for criminal organizations. The conflict and the government’s response had also forced thousands of Mexicans to seek refuge in other parts of the country.

At the same time, a number of big ticket items under the massive U.S. aid package known as the Mérida Initiative had just been delivered to Mexico, and the U.S. desperately wanted to see signs that Calderón’s government could subdue the violence, put a dent in the drug trade and, most especially, arrest and imprison the cartel “kingpins” responsible for most of the carnage.

The violence had become especially acute in Michoacán, Calderón’s home state, where a 2009 government crackdown on narcotics-related corruption, primarily targeting members of the opposition Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), had fizzled after all the detained officials were released for lack of evidence. With his own sister then gearing up to run for governor of the state, Calderón was under considerable pressure to show progress in Michoacán.

Under the circumstances, it was welcome news when it was reported, in December 2010, that Mexican security forces had killed one of the country’s most infamous cartel capos in a bloody shootout. The apparent death of El Chayo, spiritual leader of the narco-evangelistic drug gang known as La Familia Michoacana, came at just the right time. It was the first clear evidence that Calderón’s strategy, and the U.S. intelligence and military aid behind it, was working. In a “Secret” cable sent just days later, U.S. Ambassador Carlos Pascual called the killing of El Chayo a “needed win” for the Mexican president.

The Michoacán Operation was coordinated by the now-defunct Ministry of Public Security (SSP), and according to a declassified report from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), was driven by intelligence pointing to El Chayo’s location “near Holanda, Michoacan” about a week earlier. The assault on La Familia was the “largest air mobile operation” ever conducted by Mexican security forces, according to another Embassy cable, bringing some 800 federal police to the beleaguered state of Michoacán. It also relied on one of the most important, and expensive, deliverables of the Mérida aid package: a fleet of high-tech Blackhawk helicopters that had arrived only two weeks earlier, according to the same cable:

Just two weeks after they were formally handed over to the [Mexican government] on November 24, the M-qualified SSP aviation crew used three Merida Initiative-funded UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters in the Michoacan operation, substituting one for another as shootouts with LFM [La Familia Michoacana] gunmen sidelined a helicopter for repairs. Federal forces used tactical training provided under the Merida Initiative to deploy from the helicopters into difficult-to-reach places in Michoacan’s rugged mountainous terrain.

The Embassy report praised the operations that were thought to have resulted in the killing of Moreno as “a potent reminder that USG and GOM investments in Mexican law enforcement entities are gaining traction as [Mexican government] institutions are emerging with stronger capabilities to effectively combat the violent drug cartels.”

The government offensive against the cartel had also produced plenty of collateral damage. The Embassy noted that it had “led to violence across the state in the days after,” and had “caused both civilian and police deaths.” But the Embassy still judged the operation as “an overall success” for Calderón “and a serious blow” to La Familia. In killing Moreno, the “SSP [had] demonstrated its growing ability to execute complicated missions,” according to the report signed by Pascual.

While the U.S. State Department and the DEA have released some information about the 2010 operation in Michoacán, other U.S. agencies have been much less forthcoming. Just last week, the Federal Bureau of Investigation sent us dozens of redacted pages, revealing no substantive information, in response a similar FOIA request to that agency.

Pingback: Déjà vu in Mexico: Declassified Documents on the First Time Mexico “Killed” “El Chayo” | UNREDACTED

Pingback: Dark Clouds over Sunshine Week as Network Fires Mexico’s Leading Investigative Team | Migration Declassified

Pingback: Dark Clouds over Sunshine Week as Network Fires Mexico’s Leading Investigative Team | UNREDACTED